|

China : Yúnnán Shěng

15.0 km (9.3 miles) SW of Agang, Yúnnán, China

Approx. altitude: 2029 m

(6656 ft)

([?] maps: Google MapQuest OpenStreetMap ConfluenceNavigator)

Antipode: 25°S 76°W

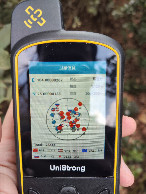

Accuracy: 5 m (16 ft)

Quality: good

Click on any of the images for the full-sized picture.

| 25°N 104°E |

(visited by Xinhao Cheng and Jing Cheng) 18-Feb-2026 -- Violent Deep Time and Serene Remnants Setting out from Kunming today, I sought to visit two specific coordinates: 25°N 104°E and 26°N 104°E. These points hold a dual significance for me. First, they are inextricably linked to Xu Xiake. In the final years of his life, Xu departed from his hometown of Jiangyin, journeying westward in a "ten-thousand-mile expedition" that eventually reached the furthest frontiers of the Ming Empire. For roughly twenty months, he trekked through what is now Yunnan Province. His journey took him from Guizhou into Yunnan, through Kunming, south to Jianshu, then east through Guangxi Prefecture (present-day Luxi), Shizong, and Luoping back into Guizhou, before finally veering northwest toward Qujing. A primary objective of this labyrinthine journey was to trace the headwaters and courses of the North and South Pan Rivers, the upper reaches of the Pearl River system. While the first volume of his Yunnan Diaries was tragically lost, the second volume opens with his observations traveling from Luxi through Shizong toward Guizhou. This path lies a mere twenty kilometers south of the 25°N 104°E coordinate. Furthermore, the source of the Nanpan River he so desperately sought is located at Mount Maxiong in Zhanyi—very close to what he identified as "north of Yanfang Station in Zhanyi." The coordinate 26°N 104°E sits squarely within this region. The second significance lies in the landscape itself—a tapestry of red soil and limestone that bears witness to a violent geological past. The Permian limestone was once a marine deposit, while the red soil originated from the weathering of the Emeishan Basalt. Approximately 260 million years ago, at the end of the Permian period, massive volcanic eruptions formed a "Large Igneous Province" covering nearly 500,000 square kilometers, stretching from central Sichuan to southeastern Yunnan. It was this tectonic upheaval that served as the prelude to the Permian-Triassic extinction event. Over eons, this basalt was weathered and eroded, leaving behind insoluble iron and aluminum oxides that yielded a deep crimson hue—the red soil that now blankets the karst topography. Gradually leveled by tens of millions of years of wind and rain, and subsequently uplifted by the Himalayan orogeny, the region became a peneplain (ancient planation surface) at an altitude of nearly 2,000 meters. It no longer resembles a typical rugged highland; instead, it rolls onward like a plain. Were it not for the precipitous drops at its fringes, one would hardly believe they were standing in a mountain range. It is precisely the existence of these vast peneplains that allows Yunnan’s mountains to nourish tens of millions of people from diverse ethnic groups. My longitudinal traverse from 25°N to 26°N today is, in essence, a journey through this thin membrane woven from red soil, limestone skeletons, and "Deep Time" memories. My father and I began our journey at 9:00 AM, driving east from Kunming along the Shunkun Expressway. This region was relatively unfamiliar to us, making it a journey of constant surprise. En route, we crossed the Luliang Basin. Here, the typical ravines of Yunnan abruptly vanish, replaced by a vast, seemingly boundless flatland. The sheer scale is staggering—it feels far larger than the intermontane plains of Kunming or Dali. I later learned it is the largest basin in Yunnan, exceeding 700 square kilometers. This area represents a subsided block from the orogeny, subsequently filled and leveled by washed-in red soil and debris. The South Pan River, originating in Qujing, flows north-to-south through this basin before carving a deep canyon on the western edge as it descends toward the lower elevations of Yiliang. The expressways here are straight and wide, "luxuriously" designed with six lanes. We gathered speed, leaving the flats after half an hour to turn onto the rural roads nestled within the folds of the Mile-Shizong Fault Zone. The road tightened instantly, making passing difficult, while the scenery shifted into limestone hills draped in red earth and vegetation. Had we continued northeast, we would have seen these hills transition into classic karst topography, riddled with peak forests and sinkholes. Over three hundred years ago, Xu Xiake precisely recorded this transition: "Parallel to the ridge toward the east, the land is pockmarked with pits and hollows—the smaller ones like dry wells, the larger like basins—all filled with dense, impenetrable thickets. The peaks are thick with trees and stones, unlike the earthen mountains and grassy ridges of Shizong." While we did not witness this specific transition today, we turned north at Sizhuang Village, ascending toward 25°N 104°E. Satellite data places this point on the northern flank of the ridge, marking the northernmost fringe of this fault zone’s folds. The mountain road was steep and winding, though fortunately brief, and we soon reached the ridge. Just as Xu described, while limestone outcrops appear occasionally, most of the ridge is carpeted in red soil. Gentle slopes have been reclaimed as farmland, while steeper inclines are thick with cogon grass and shrubs, interspersed with low trees. The most prominent "flora" here, however, are the wind turbines erected over the past decade. Their blades let out a low, rhythmic moan as they catch the mountain gusts—a sight that has become a quintessential feature of the Chinese landscape. Parking near a turbine tower, I walked north along a trail. Following my GPS signal, I moved through one field, then climbed into another at a higher elevation, until finally, the signal led me into a thicket at the edge of the field. Finding a small gap, I pushed through the branches until the decimal points of my coordinates finally hit zero. Here, the cardinal directions dissolved into an indistinguishable tangle of leaves and twigs. I moved a few meters back out of the thicket to capture the surrounding landscape: woods to the east and west, red earth and slopes to the south, and to the north, looking down the mountainside, the endless, sprawling ancient peneplain. At that moment, the crackle of firecrackers echoed from a nearby gully, followed by voices and the silhouettes of a family. I packed my gear and caught up with them; they were local villagers who had come, according to tradition on the second day of the Lunar New Year, to visit ancestral graves. Eventually, an elderly woman asked the inevitable question: "What are you doing here?" I explained that this was a crossing point of integer latitude and longitude lines, and I had come simply to see it. She seemed only half-comprehending but replied with a smile, "Good, that's good." More firecrackers sounded in the distance. Here, standing amidst this landscape and contemplating the past, I was clearly not the only one. The journey continues toward 26°N 104°E. |

| All pictures |

| #1: the general area #2: east view #3: north view #4: south view #5: west view #6: GPS view #7: wind turbine ALL: All pictures on one page |